Kettle the Lightning Bolt had a brief but electrifying life.

Lightning bolts don’t have names or genders. But for the sake of this story, meet Kettle. He was born on July 21, 2013 in the skies above Kettle Moraine State Park in southeastern Wisconsin. The weather forecast that afternoon called for partly cloudy skies, a high in the 80s, and 90 percent humidity – ideal conditions for brewing a lightning bolt.

The weather was hot and muggy, but that did not deter Wisconsin trail riders from enjoying the day at the park. The trail system at the park connects to the Ice Age National Scenic Trail, a meandering route nearly 1,200 miles long that traces the edge of an area once covered by a prehistoric glacier. When it receded long ago, the glacier left hillock formations called “moraines,” topography that makes for great trail riding. Horsemen travel from across the Midwest to ride in the park. Those who don’t own horses can hire outfitter Tonya Lee, owner of Dream A Horse riding stables in nearby Eagle, Wisconsin.

That afternoon, Lee saddled six horses and hauled them to the Eagle Trailhead to meet a group of five riders. They went through the rigmarole of a commercial trail ride: meet the horses, adjust stirrups, sign waivers. Yes, they understood that horseback riding is classified as a “rugged adventure recreational sport activity.” Yes, they agreed Dream A Horse would not be held responsible for “elements of nature that can scare a horse.” They saddled up and rode down a trail shaded by towering pine trees.

Unbeknownst to them, climatic forces were at work to bring Kettle the Lightning Bolt into the world. Twenty thousand feet into the atmosphere, the sun heated a rising column of humid air. Water molecules condensed into snow and ice crystals, forming a cumulonimbus cloud that was visible from the ground except where treetops obstructed the view.

Lee rode at the head of the group. Last she had checked the sky, a few puffy white clouds floated in a sea of blue. She had no reason to worry about inclement weather. But 15 minutes into the ride it started to sprinkle.

“It was a really hot day, so we didn’t mind,” Lee later says.

The sprinkle soon became a downpour of rain mixed with hail, and water quickly pooled 6 inches deep on the trail. Lee knew it was time to turn back, and the group took a shortcut back to the trailhead.

At that moment, Kettle was nothing more than a legion of positively charged ions and negatively charged electrons racing around like hyperactive kids on skateboards. The rambunctious particles fed off each other, building an energy field that the cumulonimbus could no longer contain. In an instant that science doesn’t fully understand, the bottom of the cloud burst open and a gang of negative electrons stormed out.

Hello, Kettle the Lightning Bolt.

He raced to earth on a channel of ionized air. I picture him as the superhero Iceman, shooting a path of ice ahead of him to slide across. Except that Kettle’s temperature was around 53,540 degrees Fahrenheit – four times that of the sun’s surface.

“I saw a bright light and heard a big ‘pow,'” Lee remembers.

A lightning bolt’s path is hard to predict. As a rule, electricity follows a path of least resistance, meaning air and water are preferred media. Kettle zigged and zagged through the air like a playful colt at pasture. The lightning bolt threaded the needle between the pine trees and hit ground on the Eagle Trail. At impact, Kettle measured about 1 billion volts. But the lightening bolt quickly dissipated as it radiated through the earth and standing water. In less than a millisecond, Kettle traveled 20 feet down the trail to Lee’s group.

Winston Churchill once said, “There is something about the outside of a horse that is good for the inside of a man.” The opposite was true for Kettle. He struck the rear horse, a Quarter Horse named Scarlet, entering her body where her hind leg was submerged up to the fetlock in standing water. Witnesses later recalled burning smells, like sulfur, singed hair and scorned flesh.

We can only speculate the path Kettle took traveling through Scarlet’s body. But because blood is about 80 percent water, the lightning bolt likely raced through her network of veins and arteries, following them like a trail system. We do know that he exited through her mouth and temple, where Kettle connected with Scarlet’s metal bit and the decorative ponchos on her bridle. Then, the lightning bolt leap-frogged his way down the line of horses.

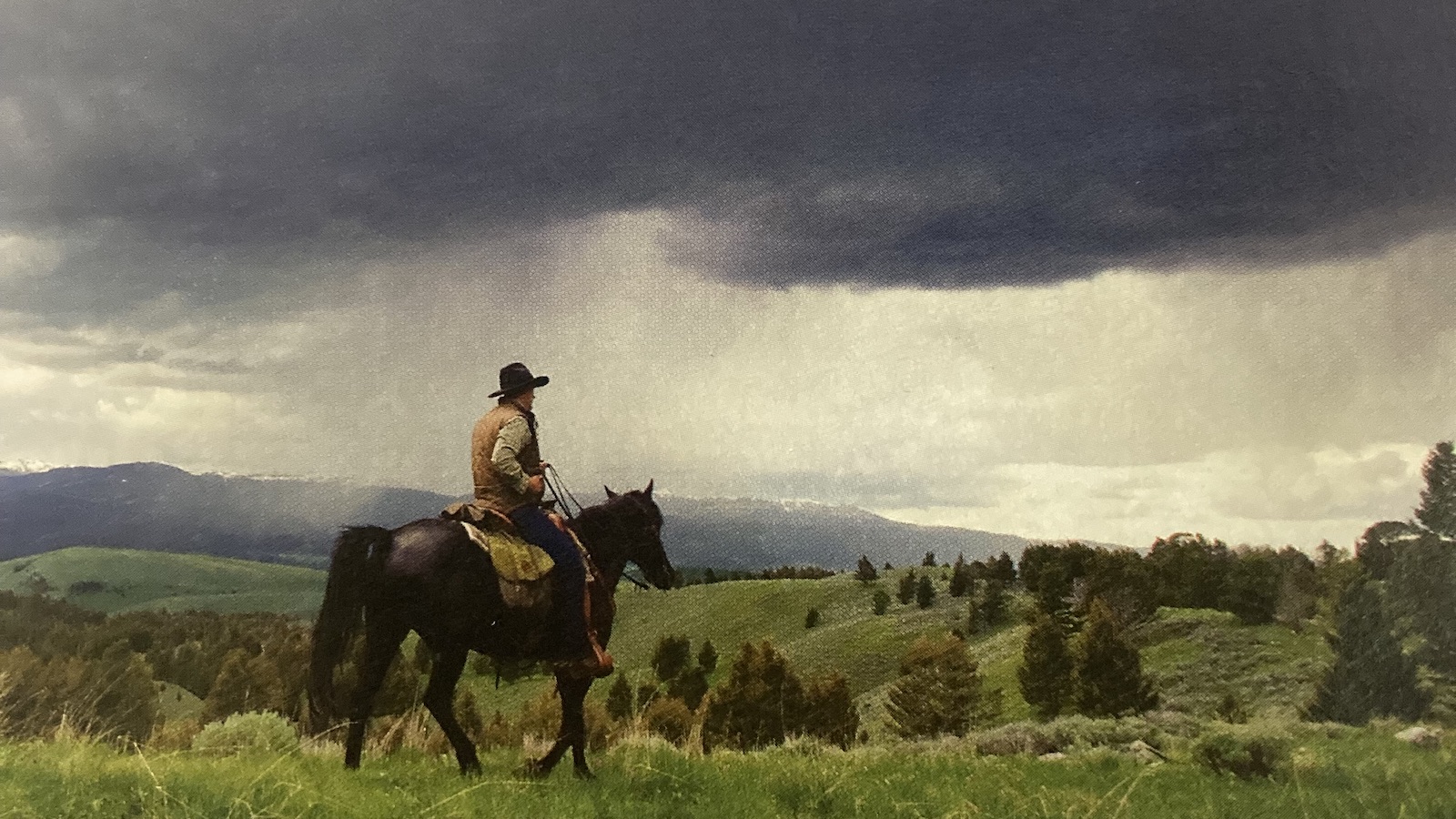

According to a report from the National Weather Service, farming and ranching ranked as the most dangerous occupations for lightning deaths for the period between 2006 and 2012. Of the profession’s 11 deaths, several were people on horseback. In 2008, a sheepherder and his horse were struck dead while riding her in the Rocky Mountains of southern Colorado. In 2010, an Idaho cowboy and his horse were struck while rounding up cattle. Ditto for a Montana rancher and his horse in 2011. Lightning bolts don’t discriminate, but clearly horseman are at an increased risk of exposure.

Electrocution causes muscles to spasm. Scarlet reared and fell, landing on her rider and fracturing the woman’s eye socket. Both of them were knocked unconscious. The next horse fell sideways, and the third collapsed to its knees. Both of their riders were able to dismount. Kettle had vanished by the time he reached the head of the string.

“When I turned around, I saw three of my horses on the ground,” Lee says.

One year later, Lee’s horses have recovered from their burn injuries. One horse developed an irregular heartbeat that has since stabilized. The rider who was crushed was taken to the hospital and released the next day. The first thing she did was visit Dream A Horse stables to check on Scarlet. The mare had taken the brunt of Kettle’s charge, likely saving her rider’s life, but survived. And everyone involved came away with a healthy respect for the power and unpredictability of lightning.

As for Kettle, his time on earth had lasted a brief, but quite electrifying, 0.2 seconds.

This article was originally published in the April 2014 issue of Western Horseman.