Jerry Diaz brought the pageantry of charro horsemanship to the masses. Now, as he passes the lessons of four generations of horsemen on to his young son, Diaz hopes he’ll be remembered as more than just a specialty act.

A soft mist taunts drought-stricken pastures as I make my way up the driveway leading to the Three Creek Ranch, located outside New Braunfels, Texas. In the alley of a modest barn, Gerardo “Jerry” Diaz puts his black gelding, Lucero, through his paces. The horse is featherlight as he floats from gait to gait in perfect frame.

As if whirling and dancing to music only they can hear, the pair court my attention with each graceful pass. Before my eyes, maneuvers such as the side-pass, rollback and piaffe transcend mechanics and become art.

Jerry’s position in the saddle never alters, nor does his hand move from its single position on the riendas, or reins. The “chinging” of the rein chains and Lucero’s rhythmic breathing break the silence as man and mount move effortlessly as one, each the product of years of training in traditional charro horsemanship methods.

These techniques emerged in the early 16th Century as the charro, or Mexican cowboy, honed his horsemanship skills on Spanish haciendas, and later showcased his abilities in the charreada, a type of Mexican rodeo.

The true charro is a master horseman of unparalleled ability, working with skill, elegance and dignity, performing maneuvers with a complexity rivaling upper-level dressage and a flavor influenced by generations of stockmen who depended on horses every day.

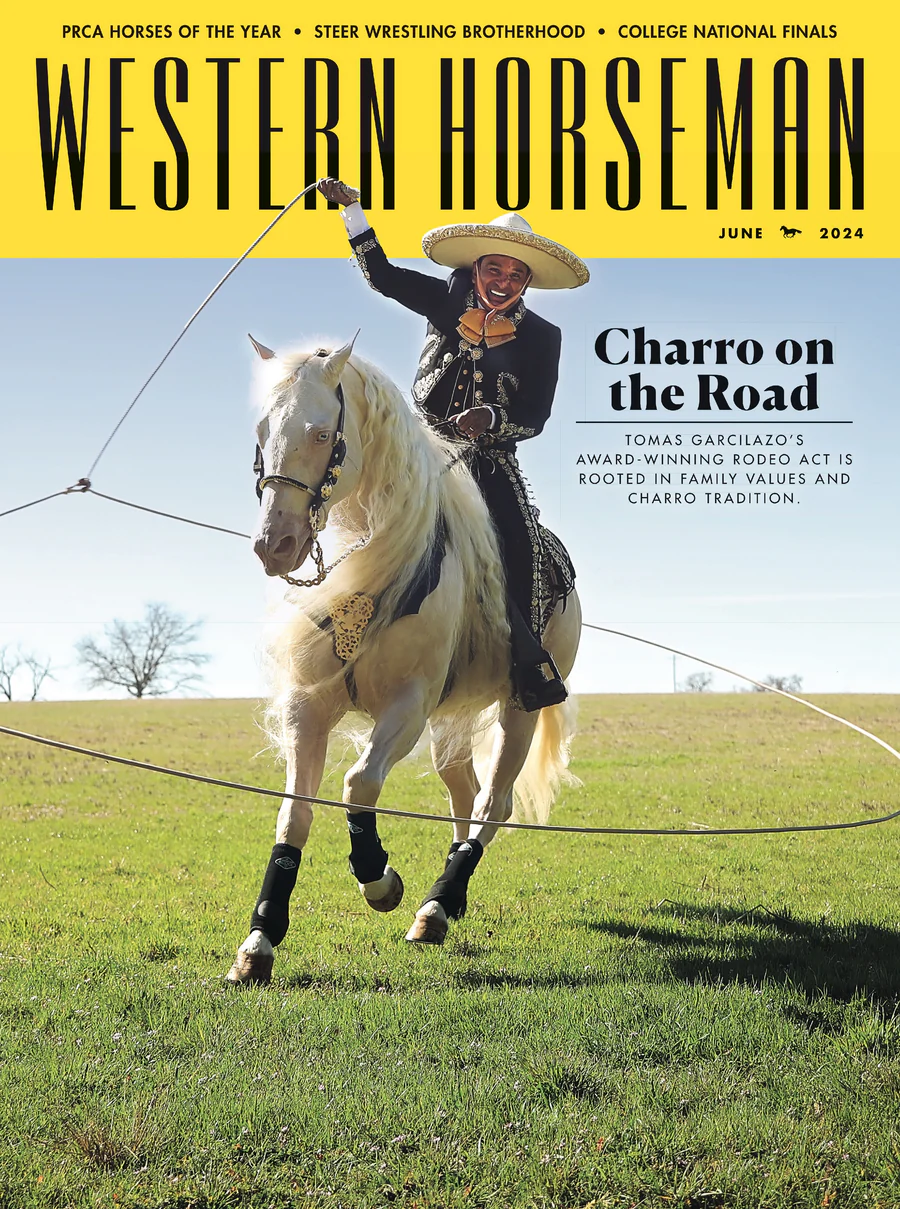

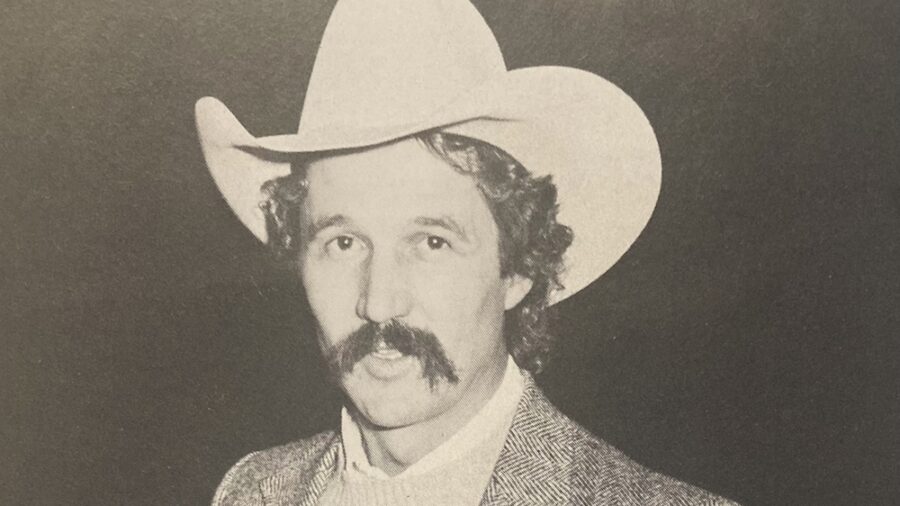

Passed down from Jerry’s great-grandfather, a Spanish horseman, and continued by his grandfather and father in Mexico, the charro way of life is Jerry’s first love, and the 46-year-old is perhaps today’s best-known charro. His sold-out extravaganzas at rodeos—from the Forth Worth Stock Show to Denver’s National Western— include spectacular displays of horsemanship, trick roping, a mariachi band and the pageantry of the Mexican and Spanish horse cultures.

A Grand Tradition

Black-and-white photographs of days long past crowd the walls in the home of Jerry’s father, Jose “Pepe” Diaz. In one, a young Jose uses the mangana [rope catch of the two front legs] to catch a wild horse from the ground. The rope is tied around Jose’s neck while his mount lies beside him, waiting for the cue to rise. The dangerous act, tiron del orchado, is still performed today.

As I marvel at this informal display of early charro history, 87-year-old Jose smiles.

Jerry, who has explained the images in detail, now translates his father’s softspoken Spanish.

“People have died from doing that,” Jose remembers. “But I never worried. I had a neck like a piece of steel.”

One of 12 children, Jose began his education on the family hacienda in Guadalajara, Mexico. Amid the political and social unrest of the Mexican Revolution, he learned to rope, ride and train horses according to charro traditions, as had two generations of Diaz horsemen before him.

Jose soon became a standout in Mexico’s popular corridas, or mounted bullfights. When he was just 19, his reputation as a skilled horseman earned him a job training horses for the family of then-Mexican President Lázaro Cárdenas.

Jose trekked north to the United States in 1948. While traveling with the Barnum and Bailey Circus, training horses for Western movies and even doubling as the Cisco Kid in a television series, Jerry’s father adhered to the strict charro code: chivalry, high ethics, expert horsemanship, and dedication to family and tradition. And, as all charros do, he projected his proud heritage through everyday manner and traditional dress.

Typical working attire includes accessories like half-chap leggings, a decorative leather belt embroidered with maguey cactus fibers, a braided rawhide cuarta or quirt, a neckerchief, and a hat held in place with a chin strap. When he performs in public, the charro strives for the height of grand elegance, donning tight trousers; a matching bolero jacket and vest, often embellished with suede and gold; a sombrero made of palm, hare or wool; silver-inlaid espuelas, or spurs; and a colorful neck scarf.

“Just because a person dresses the charro, doesn’t mean he is a charro,” Jose explains. “It has to come from the heart. Dressing the charro is something you do with pride. It signifies the maximum art of horsemanship and, even today, commands great respect.”

Jose Diaz’s love of horses is a passion he passed to his son. And, from an early age, Jerry proved a willing pupil as he sought to absorb everything he could about the charro discipline.

Jerry learned to follow the movement of the horse from the back of his father’s mount. Jose would place his 5-year-old son behind him in the saddle and then take his horse through the traditional paces—spinning, sliding, dancing, marching.

“In the beginning, my nose was always red because I banged my head up against his back,” Jerry recalls. “But after I learned to follow the movement of the horse, I stopped banging my nose so much.”

Jerry’s mother, Rosa Diaz, remembers how her son couldn’t wait for his father to come home from work so the pair could train horses.

“It didn’t matter what time it was,” she says. “Two in the morning or two in the afternoon.”

On cold evenings, fires provided light and heat by which the pair could school horses. When it rained trees and raincoats supplied protection.

“I’m never going to be half of what my dad is as a horseman,” Jerry admits.“He’s a legend and an encyclopedia of knowledge. He knows the horse’s mind and body. I have so much respect for him.”

Jose still tries to make the rounds on the ranch, moving a little slower these days, but with as much diligence as ever. Up until a recent heart attack stole his strength, the octogenarian worked side by side with his son. These days, perched in front of a large bay window in his living room, or atop a special platform Jerry built for him inside the covered round pen, Jose watches his son work the family’s horses, taking in every movement and every cue as if feeling the horses’ reactions himself.

It Has to Come from the Heart

In the crowded Diaz tack room, decorative tools of the charro trade hang like museum pieces, inviting adoration and explanation. The family’s monturas, or saddles, are the most identifiable icons among the horse gear, with their intricate hand-stitched designs fashioned from fibers of maguey cactus. Jerry’s father has worked to keep the tradition of piteado alive, embroidering the family’s saddles with traditional fretwork.

Among the gear are trophies and photographs from Jerry’s days competing in charreadas—a few salvaged from the 1998 San Antonio flood that ravaged his childhood home. Several all-around titles helped build his reputation as both an athlete and a performer, and in 1984, he drew the attention of Mary Nan West, then-director of the San Antonio Stock Show and Rodeo.

“She wanted me to perform for a group of Russian delegates,” Jerry recalls.

The Monday following that show, he received a second invitation.

“I’ll never forget the smile on Mary Nan’s face,” Jerry says. “She told me she wanted me to perform again, but this time at the San Antonio Stock Show. She was my godmother of rodeo. She sent $400 to the Professional Rodeo Cowboys Association for my permit, and that began my PRCA career.

It’s been almost 25 years since Jerry first heard his name announced in the San Antonio Coliseum, but time hasn’t lessened the passion he feels for his art.

“I still get chills,” he admits.“When I perform, it’s from inside the heart out—charro de corazon, or charro from the heart. You can feel it, and if you can’t feel it, that means it wasn’t a good show.”

Jerry’s show is a family affair that involves his wife, Staci, and son, Nicolas.

A third-generation horsewoman born into a family of performers, Staci is an accomplished trick and Roman rider, recognized in rodeo circles for her six-up American White Horse Roman team. A noted stuntwoman, she also has appeared in films including True Women, North and South and Buffalo Girls.

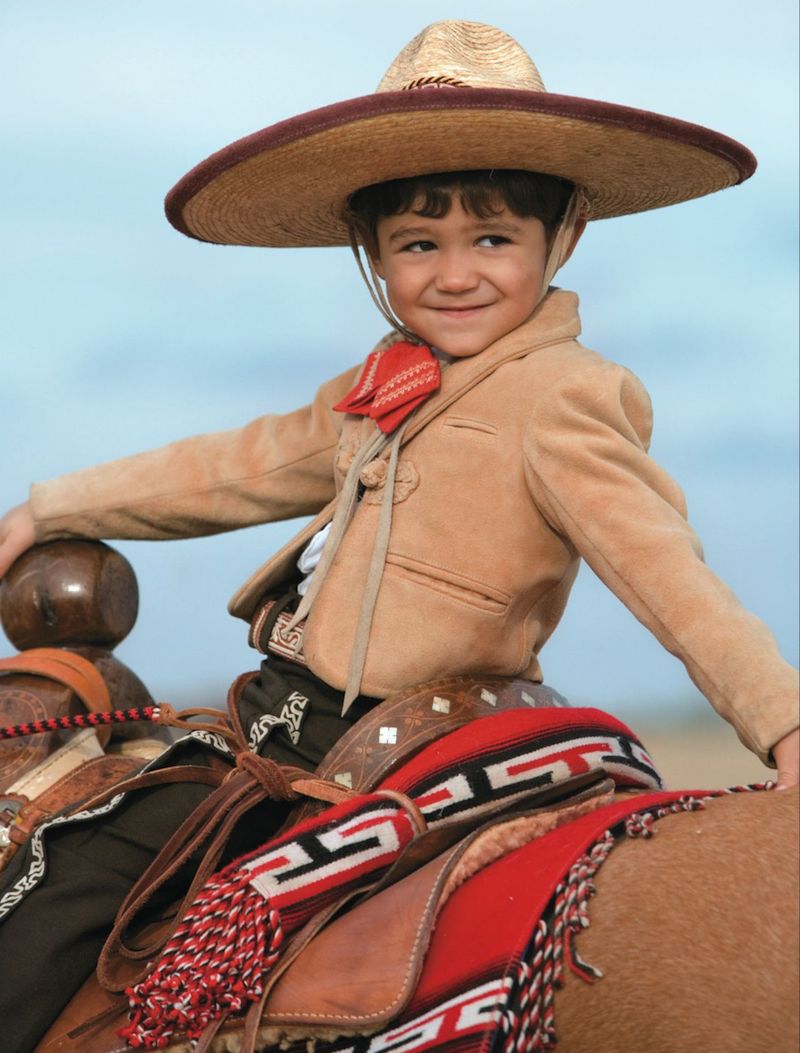

Just 3, Nicolas seems a born performer as he proudly salutes audiences from the back of his father’s horse, Grano De Oro, or “Grain Of Gold.” The family has performed together all over North America.

Elaborate rope-handling, spectacularly complex horsemanship maneuvers, and traditional music, dress and gear all factor into the “charro de corazon experience.”Jerry maneuvers a heavy, 65-foot maguey

rope with ease and grace, creating spectacular loops with colorful names such as mariposas,resortes, arracadas and cambios. His signature maneuvers include the Texas Wedding Ring, which starts with a small loop and ends with the rope encircling riders and horses at a full gallop, and jumping through a spinning loop while standing atop his horse. While roping, Jerry works other horses on the ground asking them to sit and lie down amid the activity.

The Diaz equine troupe is diverse, including Quarter Horses, Paints, Appaloosas, Andalusians and Andalusian/Quarter Horse crosses. Jerry and Staci work with as many as three stallions in each performance, adding to the degree of difficulty.

“We spend a lot of time training our stallions to work together,” Jerry says.“Stallions are hard to deal with. They’re beautiful, with fantastic power and presence, but also dangerous.

As amazing as the shows are, the horsemanship behind them is equally impressive. Spectators, fans and fellow trainers often ask Jerry to share his secrets.

“The secret is raising our own horses,” he explains. “Short-term doesn’t work; long-term does. You are a part of the horse’s life, and he is a part of yours.”

The Little Charro

In the quiet of the waning Texas afternoon, Jerry and Jose hide from the sun in the shade of the family’s indoor arena. Staci, Nicolas and I join them, cool beverages in hand. As we each take in the final minutes of the day’s visit, Jerry shares a thought about the future.

“I want people to remember me as an artist and a performer, a charro who loved with passion his horses and his culture,” he says.“I don’t want to be remembered as a guy who went out there with a horse and a rope—a great act.”

Jose nods in agreement as Jerry turns the subject back to young Nicolas.

“I want to be a leader for my son,” he says.“I want him to share the same kind of relationship my father and I have. Whatever he decides he wants to be, I will support him. I just don’t want him to forget his tradition and where he comes from.”

As I drive along the ranch’s gravel road, heading back toward the highway, I’m reminded of a scene from earlier in the day: Nicolas Diaz twirling his rope in the family’s yard. Dressed in his black trousers, boots and white shirt, and wearing his traditional belt, neck scarf and sombrero, he is a miniaturized version of the charro. A shy smile crosses his face when he catches me watching.

In the background, I notice the knowing eyes of Jose Diaz studying his grandson with adoration and pride. There, in the chasm between youthful interest and seasoned experience, the charro tradition is alive and well.

This article was originally published in the April 2007 issue of Western Horseman.

What a surprise and joy to read your stories about the men and women that formed the land we ride on.

Thank you.

Rosie Blount